ND-GAIN focuses on building resilience to climate change as a critical component to better prepare humans and their environment for the next 100 years. Our mission lies in enhancing the world’s understanding of the importance of adaptation and of facilitating private and public investments in vulnerable communities. For the 2014 Annual Corporate Adaptation Prize, we received 20 applicants, either multinational corporations or local enterprises working on a project in a country ranked below 60 on the ND-GAIN index and collaborating with local partners. Applications are judged on their measurable adaptation impact, scalability and market impact. Here is a brief view of two projects our applicants are employing to improve human health in Haiti and Bangladesh:

Abbott, Partners in Health & the Abbott Fund

Source Abbott

Abbott has teamed with Partners in Health (PIH) and the Abbott Fund to alleviate malnutrition in Haiti’s Central Plateau—the country’s poorest region, which also is prone to severe and deadly natural disasters. Based on ND-GAIN data, Haiti is the 15th most vulnerable country and the 30th least ready country. The country’s score has trended upward over the past 10 years, from 41 in 2005 to its peak at 46 in 2010, but has dropped slightly to 45 after the 2010 earthquake.

Source Abbott

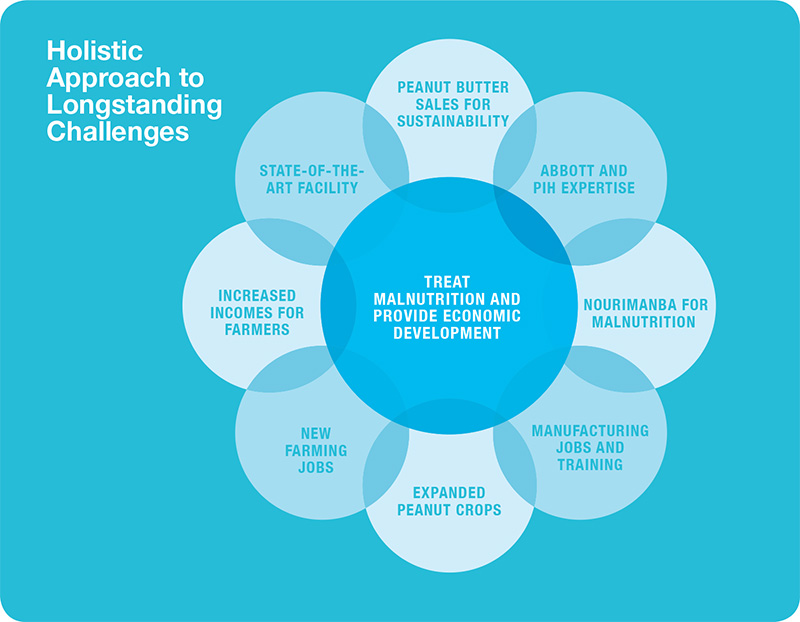

The partnership has built and opened a new facility operated by Haitians to produce Nourimanba, PIH's free and life-giving treatment for severe malnutrition in children. The partnership's agricultural development program also is helping local farmers supply the facility with high-quality peanuts, while raising farmers’ incomes. Today, the facility concentrates on producing Nourimanba and is assessing options to produce fortified peanut butter that can be sold in Haiti. They seek to create a self-sustaining social enterprise that supports facility operations and helps drive local economic activity.

BASF Grameen Limited

Source BASF

To date, the facility has produced more than 60,000 kgs of Nourimanba and has treated about 6,000 patients. It has more than 40 Haitians on staff, with additional staff hired as the plant expands. In 2014, the project hopes to increase farmers’ income by 300 percent. The partnership is working with non-profit TechnoServe to provide nearly 300 local farmers with tools such as financing for seeds, supplies, and services to increase quality, and yield by 33 percent. The Abbott Fund has provided more than $6.5 million in funding, and the facility is owned by PIH, which works together with its sister organization, Zanmi Lasante. Visit the Abbott Fund website to learn more, and view this 2012 New York Times article on the PIH website.

BASF Grameen Limited is improving human health by preventing the spread of mosquito-borne diseases in Bangladesh. It has established a joint venture social business with Grameen Healthcare Trust, a nonprofit organization created by the Nobel Laureate Professor Muhammad Yunus, to help manufacture and distribute sturdy mosquito nets to vulnerable communities. The goal is to help the country achieve its UN Millennium Development Goals. Bangladesh has a gain score of 47.3 and has been steadily improving since 2005. The project hopes to further improve Bangladesh’s mortality index and external health dependency index.

With an initial investment from BASF of €200,000, the joint venture social business employs local community members in Bangladesh and sources from local suppliers where available.

The Interceptor mosquito net was the first product of this venture, which aims to reduce mosquito-borne disease, thus contributing to achieve key U.N Millennium Development Goals related to health. In 2011, BASF Grameen provided Interceptor nets to students from Dhaka University, the largest public institute in Bangladesh. Since then, BASF Grameen has constructed a plant within Bangladesh to make and distribute these nets to communities in need. According to the WHO, the protection provided by these nets against the mainly night-active vector mosquitoes is the most effective means of preventing malaria infections. The decrease in cases of malaria in Bangladesh by 70 percent over the past five years can be attributed, in large part, to the long-lasting insecticidal mosquito nets, which retain their protective properties for up to 20 washes, depending on local conditions.

Despite Bangladesh’s upward trend on the ND index, it maintains a high vulnerability and low readiness and needs investment and innovations to continue to improve. BASF Grameen Limited’s vision for the future is to scale up its operations within Bangladesh and also address similar issues in other vulnerable countries. Visit the Grameen Creative Lab and Yunus Social Business websites for more details and to learn about their other projects. This information was compiled with the help of Sophia Chau, Intern, ND-Global Adaptation

By Joyce Coffee

By Joyce Coffee

Joyce Coffee, Notre Dame Global Adaptation Index Managing Director, opens last year’s ND-GAIN Annual Meeting.

Joyce Coffee, Notre Dame Global Adaptation Index Managing Director, opens last year’s ND-GAIN Annual Meeting.

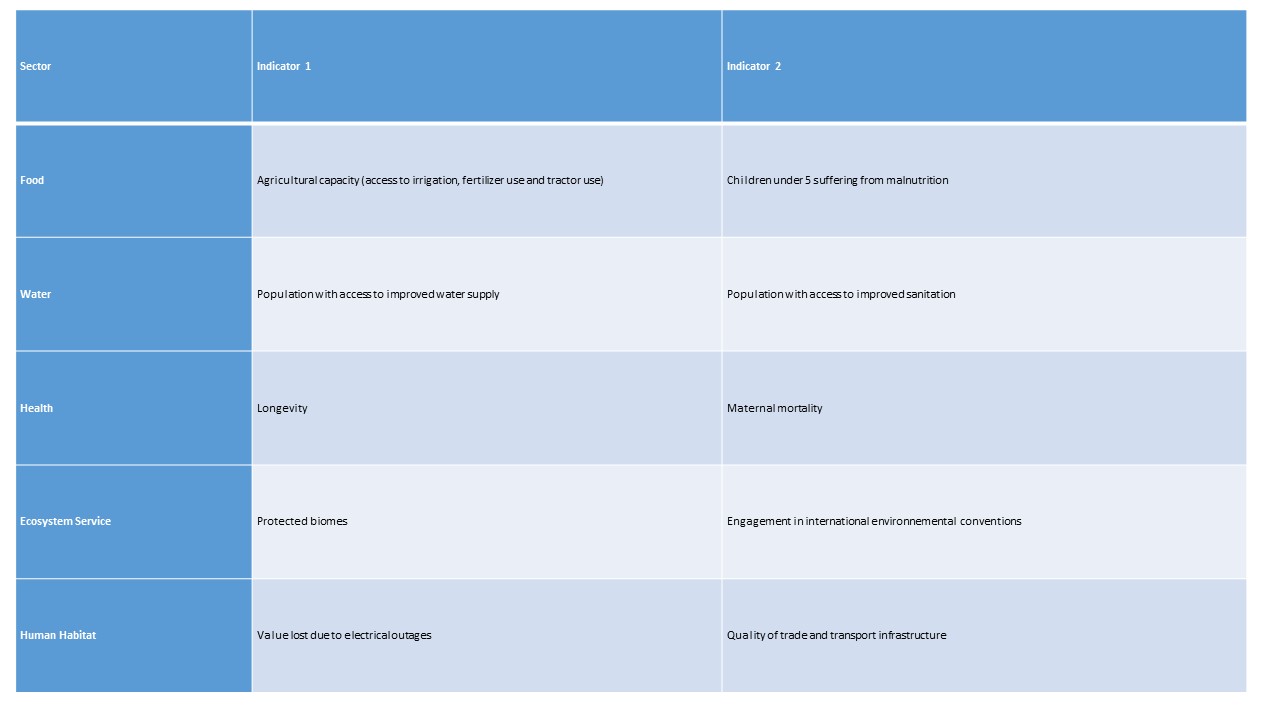

To measure countries’ resilience to rebound from adverse impacts of climate change, ND-GAIN focuses on the adaptive capacities of five sectors that provide communities with life-supporting assets and social services:

To measure countries’ resilience to rebound from adverse impacts of climate change, ND-GAIN focuses on the adaptive capacities of five sectors that provide communities with life-supporting assets and social services: