Congratulations, Mayor Lightfoot on your inspiring inauguration today. It was an honor to serve on your transition team. Here are some resilience-specific recommendations for Chicago.

TO: Mayor-Elect Lori Lightfoot via

FR: Joyce Coffee, president, Climate Resilience Consulting

RE: Environment Transition Committee Memo

DT: April 15, 2019

What is happening today that we need to keep:

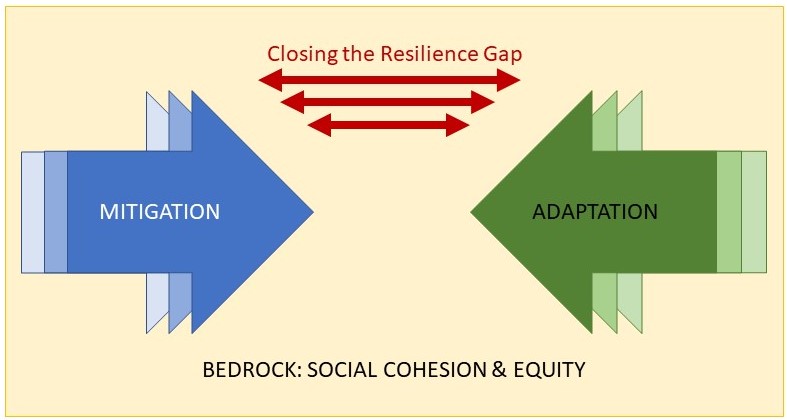

We have no time to waste on decreasing greenhouse gas emissions to save lives and improve livelihoods, thus increasing the efficacy of our climate resilience actions. For assets the City of Chicago owns, one of the swiftest, most efficient ways to decrease our carbon footprint is to purchase renewable energy credits in the near-term while planning for mid-term investment in renewable energy developments that foster jobs, air quality improvement, resiliency and economic vitality.

The City should fulfill its commitment to power public buildings with 100% renewable energy by 2025 and meet demands of the Renewable Chicago city/stakeholder working group. Its intent is to create a renewable energy transition that centrally positions social equity and environmental justice within cost-conscious energy supply arrangements to provide maximum benefit to Chicagoans.

Illustrative immediate next steps:

- Continued development of a robust database of City facilities including energy consumption and cost data to facilitate maximum monitoring and planning for energy efficiency and renewable energy investments at City-owned assets (carbon footprint related).

- Continued exploration of innovative energy procurement strategies through the active RFI for Municipal Electricity Supply and the Chicago Solar Ground Mount Project that is underway and will inform a five-year renewable energy transition plan.

- Negotiating emergent partnerships, such as the Bloomberg American Cities Climate Challenge, toward arrangements that direct philanthropic resources to areas of need.

- Finalizing the multiyear and multipronged clean energy transition plan, including the initial City renewable energy credits’ purchase as a first step in the transition.

Expected Outcomes:[1]

- Chicago’s strong contribution to slowing the rate of global climate change at levels that meet or exceed the Paris Climate Agreement.

- Improved stewardship of City assets and taxpayer dollars through expanded energy management and recognition (e.g., ENERGY STAR, Better Buildings Challenge).

- Recognition of Chicago as a global clean energy transition leader with particular innovation in bringing opportunity to communities most affected by industrial pollution.

What we need to implement immediately; or within the next year:

As a global city, Chicago is impacted by global finance trends, including at least four of which relate to climate resilience:[2]

1. Credit rating agencies evaluate the physical impacts of climate change on municipal, utility and corporate ability to pay back debt.

2. Big data informs investors about the costs of exposure to predicted future climate change.

3. Case and constitutional law includes liability for climate change risk, since predicted scenarios are now readily available and force majeur is no longer a viable natural disaster plea.

4. The Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosure has issued guidelines describing the requirement to assess investment portfolios’ risks from climate change’s physical impacts, influencing trillions of dollars of assets under management.

Fortunately for Chicago, this all equals good news. Although lower-resourced Chicagoans especially suffer from needless exposure to many environmental hazards, Chicago’s climate change hazards are significantly less than our sea coastal, drought-prone and wildfire interface neighbors elsewhere in the country. Thus, when considering the above four points’ effects on other U.S. cities, our credit ratings will not be negatively impacted by climate change; our 10-30 year infrastructure cost/benefit analysis needs will be less; we will incur less climate change-related liability; and investors in both public and private assets will have fewer physical risks to account for. The bottom line: In terms of climate change resilience, we can develop a mindset shift and brand ourselves a city more attractive to assets under management wishing to avoid risks. Therefore, we can fund resilience improvements that benefit the lives and livelihoods of Chicagoans (and, see below, our new neighbors).

Illustrative immediate next steps for the City and its collaborations with sister agencies and districts:

- Increase resilience project bankability/investability through changes to utility rate structures based on social equity considerations and more reflective of service delivery’s true costs.

- Increase cross-department resilience project pipeline identification, as well as collaborative implementation, to further collateral benefits generated by rate-based department budgets.

- Consider issuing green revenue bonds for resilience investments.[3] to attract new investors to the City of Chicago, free up more GO and other City assets for social safety net priorities, and further the City’s brand as a more climate resilient place.

- Investigate evolving risk transfer options (including parametric insurance and cat bonds), using brokers to model risks and secure the best deals, ensuring the right cover for the right price and building requirement for resilience, based on risk, into insurance contracts.[4]

Expected outcomes:

- Stable municipal credit ratings.

- More City money available to serve constituents.

- Less City revenue, livelihood and life lost from shock (e.g., extreme precipitation) and stress (e.g., extreme heat) events.

- More resilience mainstreamed in City’s essential/critical infrastructure.

- More interdepartmental project collaboration to increase value of city services for Chicagoans.

- Fewer Chicagoans suffering from flooding and extreme heat, more Chicagoans benefitting from better, water, transit, public health services.

What we can plan for longer-term implementation:

Compared to other major American cities, Chicago in coming decades will be distinctly positioned to receive our neighbors forced from their communities by rising sea levels, more extreme coastal storms and more wildfires. If we create a resilient city for our current residents, Chicago will be a fantastic receiving community for the next great migration – an estimated 13.1 million people on the move by 2100[5] from America’s vulnerable sea coasts and hot spots.

The transformation required to create this amazing place for our new neighbors should bring elements of restorative justice to our lower resourced (nonwhite, recent immigrants, non-English speakers, poor, chronically ill, female-headed households and renters) communities, providing quantifiable benefits to our current residents. https://resilient.chicago.gov/ is a good guide for programs, partnerships and policies that will greatly contribute to lives and livelihoods of Chicagoans.

In addition, recommendations from other transition committee policy areas will create resilience (e.g., Business, Economic and Neighborhood Development; Public Health; Education; Public Safety and Accountability; Housing; Transportation and Infrastructure; Good Governance; Arts and Culture and Youth).

The key is to act on the knowledge that lower resourced communities suffer most from climate and weather hazards,[6] experiencing more damage and possessing less political clout to advocate for fixes.[7]

Immediate Next Steps:

- Provide each department with a map of Chicago’s poverty by neighborhood, and ask department heads to identify their plans to create social equity in their budgets, provisioning best-in-class public services in lower resourced communities.

Expected Outputs:

- Social equity based budgets and work plans for Chicago’s departments (and sister agencies).

Expected Outcomes:

- Chicago neighborhoods offer safety, security, stability and joy to residents and welcome all, including lower resourced Americans, who have lost their family wealth due to climate change impacts.

Disclosure: I, Joyce Coffee, President of Climate Resilience Consulting, work with institutions that focus on actions recommended in this memo.

This memo was first published athttps://bettertogetherchicago.com/wp-content/uploads/Environment_Memos.pdf

[1] Expected Outputs:

-City facility and energy database that allows effective planning and transparent tracking of progress towards 100% renewable energy through efficiency, renewable development, and enhanced energy procurement

- RFP for energy supply services in 2020 and beyond that incorporates innovative approaches to renewable energy development that brings job creation and other benefits to the neighborhoods most affected by climate change and industrial pollution

- Visible City-facilitated solar developments in a diverse set of Chicago neighborhoods, including vacant and brownfield sites

- Foundation resourcing and partnerships that augment the planning and capacity of City personnel and contractors

- REC ownership that demonstrates achievement of an early milestone in Chicago’s 100% renewable energy transition

[2] Illustrative references: https://www.spglobal.com/_assets/documents/corporate/ratingsdirect_pluggingtheclimateadaptationgapwithhighresiliencebenefitin.._.pdf; https://www.spglobal.com/_assets/documents/corporate/ratingsdirect_pluggingtheclimateadaptationgapwithhighresiliencebenefitin.._.pdf;

https://www.clf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/GRC_CLF_Report_R8.pdf

https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/

[3] https://www.climatebonds.net/adaptation-and-resilience

[4] https://www.willistowerswatson.com/en-ID/Home/Services/Services/catastrophe-bond-consulting

[5] https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3271

[6] https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/when-storms-hit-cities-poor-areas-suffer-most/?fbclid=IwAR0N-Ouo0hrtHPnR-Q-lpcbYYwA0yc6NV4vWcPprQ_QoeQ-OVG0krrlO5Rg

[7] https://www.nap.edu/read/25381/chapter/6#54 and https://anthropocenealliance.org/higherground